Psychological Impact of Skin Disorders on Patients’ Self-esteem and Perceived Social Support

Charalambos Costeris1*, Maria Petridou2, Yianna Ioannou1

1School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Department of Social Sciences, University of Nicosia, Cyprus

2Department of Psychology University of Cyprus

Abstract

Background: At early developmental stages, patients’ sense of self develops under the influence of dermatological disorders and can affect how young patients perceive themselves, as well as the way they interact with those around them. Objective: To investigate the influence of dermatological disorders on self-esteem and perceived social support in two groups of patients with severe visible facial acne and with non-visible psoriasis/eczema. Design: The study engaged patients during their visit to the Dermatologist to seek treatment (prior to dermatological treatment phase), and at a six-month follow-up, when their treatment was completed (post-dermatological phase). Setting: Patients from two Cypriot cities were diagnosed with acne, psoriasis/eczema by their Dermatologists and were encouraged to participate in the study. Participants: 162 adult participants (18-35 years) took part in the study (n = 54 patients with severe visible facial cystic acne; n = 54 patients with non visible psoriasis and eczema; and n = 54 participants without dermatological disorder - control group). Measurements: A sociodemographic questionnaire was administered to all participants. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale and the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL-40) were administered prior to and at post-dermatological treatment phase. Results: All dermatological patients showed lower self-esteem and lower perceived social support, compared to the control group. Moreover, patients with acne appeared to have lower levels of self-esteem and perceived social support at both research phases and in comparison with the other groups. Conclusion: Patients’ self-esteem and perceived social support need to be psychologically evaluated before dermatological treatment, as well as after its completion. Findings suggest a comprehensive psychological support during the course of dermatology treatment.

Introduction

The development of self-esteem takes place along with the formation of the personality, from the first stages of development of the individual and the main influence in this process is the personal achievements and the opinion of others1. For this reason, chronic dermatological disorders, especially visible ones which affect external appearance are likely to influence patient's self-esteem. Since skin disorders such as acne, psoriasis and eczema often have an early onset in childhood or adolescence, and negatively affect how patients perceive their body, an element that is closely related to how they perceive themselves and interact with others2.

Due to the emotional impact it has been observed to have, acne has been referred to as a “psycho-traumatic factor”on patients' self-esteem and self-perception and on their interpersonal relationships3,4. Furthermore, research on young patients revealed that they recognize it not as a disease, but as a problem that required a solution5 and that the subjective severity of acne was directly associated with self-esteem. Likewise, young students with moderate/severe acne appear to have a higher psychosocial and emotional impairment, with greater effect on their self-esteem, body image and their relationships with others6. Moreover, some acne patients experience similar emotional difficulties related to their self-esteem, as high as those seen in patients with chronic illnesses7, while some express the belief that their skin condition affected negatively and permanently their personality8.

However, contradictory findings are presented in the literature concerning the self-esteem of patients with acne after the completion of their dermatological treatment. Whereas it is reported that self-esteem improves upon completion of isotretinoin pharmacotherapy9,10, Mulder et al.11 reported that after the completion of a treatment with oral contraceptives in patients with acne, the sample did not show a significant improvement in self-esteem and acceptance of their external appearance.

Concerning patients with psoriasis, many researchers consider that the specific skin disorder adversely affects patients’ self-esteem12, while it is usually accompanied by feelings of shame, embarrassment, and social stigma13. Research on the impact of psoriasis on patients’ quality of life concluded that this skin disorder is related to near-absent self-esteem14, while recent findings showed that patients experience higher levels of anger15 as well as lower levels of body image, and quality of life, compared to a control group16. Lastly, in one of the few studies investigating the experience of appearance-related teasing and bullying, among various groups of dermatological disorders (acne, psoriasis and eczema)17, it was found that this form of bullying seems to be a risk factor that impedes the development of self-esteem and the participation in social activities.

The investigation of the intensity to which different dermatological disorders affect patients' self-esteem is defined as a sensitive criterion for their psycho-emotional and psychosocial status, prior to dermatological treatment, as well as after its completion. Therefore, this study focuses on two phases, pre and post dermatological treatment phase, by using similar research tools among different groups of dermatological disorders, as well as comparing findings with those collected from a control group, which are considered important experimental aspects, in order to investigate in depth, the field of psychodermatology, since similar studies are missing from the literature.

The importance of the phenomenon of social support and its role in maintaining psychological and physical well-being, as health enhancement, is rapidly increasing in the psychosomatic literature18,19. Studies have shown that people who receive different types of support from their family, friends or significant others are healthier and cope more easily with the daily difficulties or with the difficulties caused by an illness20. Most studies focus on how social support affects patients’ quality of life or on how dermatological disorders affect individual areas of patients’ functionality, without investigating its effect on patients' self-esteem3,21,22.

For example, research has shown that social support is an important factor for the improvement of the lives of patients with acne23, whereas acne itself appears to be the most important factor that might affect patients' perceptions of their mental, social and general health3. More specifically, Al Robaee3 found that patients with acne who were married and those living in rural areas reported better overall health and this finding was justified by the fact that these two groups had better social support. In addition, Livea Lalji et al.24, suggested that in combination with pharmacological treatment, the improvement of social support and self-esteem through psychotherapy can help acne patients to adapt better to their illness.

In respect of patients with psoriasis, it is reported in the literature that in periods of time when there was an exacerbation of the skin disorder, the lack of social support not only affected patients' quality of life, but may have preceded the resurgence of the skin disorder25. Furthermore, studies have shown that some patients with psoriasis may avoid physical exercise26 and social activities, while they believe that their skin disorder also affects their sexual relations27. Similarly, the decline in the quality of life caused by childhood eczema may be accompanied by feelings of shame and school bullying, and can cause social isolation and depressive symptomatology28. Smoother adaptation to chronic illness involves finding ways to participate in social activities and for this reason social support is effective in patients with psoriasis22. Based on the aforementioned, the effect of dermatological disorders such as acne, psoriasis and eczema on patients' self-esteem needs to be investigated in combination with the social support they have at their disposal, in order to determine whether patients with low perceived social support face lower levels of self-esteem and if they have difficulties adapting to the demands and effects of the skin disorder. More specifically, the investigation of social support and self-esteem among groups with different dermatological disorders, both prior to the dermatological treatment, as well as after its completion, are absent from the literature so far. Studies that would investigate the social support and self-esteem of dermatological patients in two research phases, before patients begin pharmacological treatment with their Dermatologists and after its completion, can result in the detection of the sensitive groups of patients, who are at higher risk for developing emotional problems due to their skin disorder.

The principal aim of the present study is to examine the hypothesis that patients with severe visible facial cystic acne (Group A), as well as patients with psoriasis and eczema localized elsewhere on the body (with no visible localization) (Group B), would show lower levels of perceived social support and lower self-esteem at both research phases, prior to dermatological treatment and at post-dermatological treatment phase, and in comparison with the control group (Group C). The second aim is to examine whether patients with visible facial acne (Group A), will show lower levels of perceived social support and lower self-esteem at both research phases, compared to patients with non-visible psoriasis and eczema (Group B).

Methods

Study design

This was a study with a six-month follow-up assessment (prior to and post dermatological treatment phase). At prior to dermatological treatment phase, each participating dermatological patient had agreed with their Dermatologist to receive pharmacological treatment for their skin condition, while the post dermatological treatment phase took place six months after each participants’ pharmacological treatment was completed. Self-esteem and social support were assessed in patients from two groups of dermatological patients, from two cities of Cyprus (Paphos and Limassol), in comparison with a control group. Participants who were diagnosed by their Dermatologist with severe visible facial cystic acne and who followed pharmacotherapy with retinoids and antibiotics constituted Group A; participants who were diagnosed by their Dermatologist with non-visible psoriasis/eczema constituted Group B. These patients followed pharmacotherapy with oral medications such as corticosteroids and antibiotics, as well as topical medications such as creams, salicylic acid and shampoos. Group C was comprised of participants without any diagnosed dermatological disorder. The study and tools received approval by the Cyprus National Bioethics Committee (EEBK EΠ 2015.01.103). Participants were excluded if they were not fluent in Greek or were unable to read, if they had any medical condition that could affect their self-esteem, body image and quality of life, if they had any physical disability and in case of pregnancy.

Study population: Recruitment and screening

Participants from Groups A and B were exclusively diagnosed and informed about the research by four Dermatologists, by using snowball sampling. Despite the limitations of this method regarding selection biases and generalization, it was appropriate and purposeful sampling for the current study. Specifically, snowball sampling was selected because dermatological patients with acne and psoriasis/eczema are not easily accessible29. Therefore, it was necessary firstly to identify these patients and then to gather their responses. A consent form was provided by Dermatologists to those patients who were interested in participating in the research. By signing the consent form they agreed to be contacted by the researcher, to schedule the pre-intervention interview. Participants of Group C (control group) were selected by the snowball sampling method in order to have the same methodological design through all the phases of the research. Additionally, by using snowball sampling, the researcher can ask participants to recommend other individuals for the study. This method also provides the researcher with the opportunity to have better communication with the participants, as they are acquaintances of the first sample, which is already linked to the researcher30. However, all participants of the Group C (control group) were randomized selected from the community, since their participation was voluntary and they communicated with the researcher. During the first meeting with participants, they were provided with additional information about the study and consent was obtained for their participation in the follow-up phase, upon completion of the pharmacological treatment (6 months after the phase 1). All participants were also informed about confidentiality and their right to withdraw from the study at any time. In order to screen participants for their eligibility, their sociodemographic data were gathered through a brief interview, as well as information about the body part affected by the skin condition, its visibility and the prescribed treatment by the Dermatologist. Following this, the Rosenberg Self-esteem scale and the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL-40) were administered to each participant at the first meeting (prior to dermatological treatment phase), as well as six months after they completed their pharmacological treatment (post-dermatological treatment phase). Only one participant from Group B, did not complete their dermatological treatment. However, they were not excluded from the study, since they participated in the follow-up phase and our results were not affected by their drop out (all our analyses were run twice, with and without the specific participant).

Measures

Sociodemographic questionnaire and skin disorder characteristics

A questionnaire was developed for the purpose of this study, in the form of a short interview and was administered to all three groups of participants, only at prior to dermatological treatment phase. It consisted of closed questions, regarding participants’ demographics (age, gender and education) and characteristics of their skin disorder (age of onset, nature, body part localization, visibility and confirmation that at the stage of participating in the research they have also agreed with their Dermatologist to receive pharmacological treatment).

Rosenberg Self-esteem scale

The scale consists of 10 questions which measure a person's overall self-esteem. Using a 4-point Likert scale (where 1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Agree, 4 = Strongly Agree), participants are asked to choose whether or not they agree with the content of each statement. Half of the questions measure high self-esteem and the other half measure low self-esteem. Morris Rosenberg's scale is one of the most popular psychometric tools for self-assessment, and its validity and reliability are confirmed by the literature27, 31. This study made use of the Greek translation of the scale, since this self-report measure of self-esteem has been used in several previous studies with a Greek and Cypriot population; the internal consistency reliability of the tool scales ranged from .82 to .90. The scale was used at both research phases and for all three groups of participants.

Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL-40)

The ISEL-40 questionnaire is designed to measure people's perceptions towards their social support. More specifically, it explores the ways in which the social environment influences people's response to stressful events. It consists of a list of 40 statements regarding the availability of possible social resources, half of which are positive and half negative. The statements fall into four subscales which consist of ten statements and relate to: (a) tangible support - which explores the availability of material assistance; (b) appraisal support - which explores the perceived availability of other people, so that the individual can receive advice, guidance and information; (c) self-esteem support - which explores the perceived availability of a positive comparison when the individual compares himself to others; and (d) the belonging support - which explores the perceived availability of other people that the individual can interact with32. This questionnaire is one of the few self-report measures that evaluates social support in Greek language and has been translated and used by using the back translation method33, while its internal consistency reliability (Chronbach’s a) ranged from .81 to .89. The questionnaire was used at both research phases (prior to dermatological treatment and post dermatological treatment phase), for all three groups of participants.

Statistical analysis

In order to test the sample, all the relevant assumptions have been tested by using the SPSS 22 statistical package for Windows. Specifically, the sample distribution follows a normal distribution, which was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (D (162) = .11 p > .05) and was non-statistically significant, indicating that the sample followed the normal distribution. Therefore, ANOVA analysis of variance was considered the appropriate test for analyzing the present sample.

ANOVA analysis of variance was applied to identify statistically significant differences between the three groups, in terms of their demographic characteristics at the prior to intervention phase. Mix ANOVA was performed in order to explore differences in self-esteem and perceived social support scales, prior to and post dermatological treatment phase, between all three groups. Further, Post hoc comparisons were performed to identify differences in self-esteem and perceived social support scales among Group A and Group B. Bonferroni correction with p <.001 method was used to avoid type I statistical error. Additionally, to prevent the possibility of selection biases, due to sample heterogeneity, ANOVAs and MANCOVA analyses were performed.

Results

Sample characteristics

The study included 162 participants. Among the clinical sample of the dermatological patients who were diagnosed by their Dermatologists, 54 had severe visible facial acne (Group A) and 54 had psoriasis/eczema, which was not visible (Group B). The control group consisted of 54 participants who had no skin disorder (Group C). The age of the participants ranged between 18-35 years old (76 males; M= 24.94 years old). All the demographics are illustrated at the Table 1.

Table 1: Percentages for demographic characteristics and past therapies during pre-intervention phase baseline of the sample (N = 162)

|

|

Group A (n = 54) |

Group B (n = 54) |

Group C (n = 54) |

|

Age |

20.21 (3.40) |

28.89 (5.36) |

24.80 (3.56) |

|

Educational Level |

|

|

|

|

Bachelor Degree |

18.5% |

57.4% |

57.4% |

|

High School |

81.5% |

42.6% |

42.6% |

|

Occupational Status |

|

|

|

|

Unemployed |

7.4% |

16.7% |

1.9% |

|

Employees |

24.1% |

63.00% |

66.7% |

|

Undergraduate students |

33.3% |

11.1% |

27.8% |

|

Post-graduate students |

1.9% |

|

1.9% |

|

Soldiers |

33. 3% |

9.3% |

1.9% |

|

Economic Status |

|

|

|

|

Poor |

|

3.7% |

|

|

Middle |

16.7% |

25.9% |

20.4% |

|

Good |

55.6% |

51.9%

|

55.6% |

|

Very good |

27.8% |

18.5% |

24.1% |

|

Status |

|

|

|

|

Marriage |

1.9% |

38.9% |

92.6% |

|

Single |

98.1% |

54.4% |

7.4% |

|

Divorced |

|

3.7% |

|

|

Past therapies |

|

|

|

|

Dermatological Treatment from Dermatologists |

81.5% |

83.3% |

No data |

|

Psychological treatment |

0% |

0% |

No data |

Primarily analyses

Taking into account the heterogeneity of the demographic characteristics across the three study groups, to reduce the possibility of selection biases of our sample ANOVA analysis was run. Results showed that there were not any significant differences across the three groups in regards to gender, occupational status, and economic status (p > .05). However, there were significant differences of age F(2,161) = 48.16, p <.001, educational status F(2,161) = 12.53, p <.001 and family status F(2,161) = 13.04, p <.001. Specifically, the participants in Group A, had lower educational status and they were younger and single compared to the others two groups. These demographics differences can be explained since acne usually occurs earlier in life, during adolescence to young adulthood, when compared to other dermatological disorders. However, in order to examine whether the abovementioned demographic differences influence the dependent variables, MANCOVA analysis was performed. The analysis indicated that there were no significant effects of groups on self-esteem and perceived social support prior-to and at post dermatological treatment phase, after controlling of the demographic characteristics F(3,160) = 8.04, p = .65.

Differences in self-esteem and perceived social support between groups, prior and post-dermatological treatment

To investigate whether the two groups of dermatological patients will have lower levels of self-esteem and perceived social support, in comparison with the control group, at both research phases, repeated ANOVA measures were used with two repeated measurements. The dependent variables were the overall self-esteem and perceived social support scores. The Time factor (prior to- and post- dermatological treatment) was used as within-subjects factor and the Group as Between-Subjects factor. Through this procedure, it was examined whether the dermatological treatment influenced each groups’ self-esteem and perceived social support levels.

Table 2 shows the mean values of self-esteem (Rosenberg self-esteem scale) and perceived social support (ISEL-40), prior to- and post- dermatological treatment phase. It is observed that after the completion of the dermatological treatment, the overall perceived social support changes significantly and decreases, both for the dermatological patients (p <.001) as well as for the control group (p <.001). However, after the completion of the dermatological treatment there was no change in the mean value of total self-esteem among the two groups of dermatological patients, as well as for the control group.

Differences in overall perceived social support (ISEL-40 questionnaire) between groups, prior to- and post-dermatological treatment

The overall perceived social support in which there were statistically significant interactions between the two factors (Time and Group), suggest that group participants respond differently to the effect of Time (before and after the completion of the dermatological treatment), F (2,159) = 8.53, p <.001, η2 = .097. Follow-up pairwise comparisons reflected that in Group A, the overall perceived social support level significantly decreased from the prior-to-intervention phase (M = 106.17, SD = 14.21) to the post-dermatological-treatment phase (M = 103.52, SD = 13.64), p < .001. Also, for the participants of Group B, the overall perceived social support level significantly decreased from the prior-to-intervention phase (M = 115.26, SD = 14.24), to the post-dermatological-treatment phase (M = 113.74, SD = 14.24), p < .001. Similarly, in the control condition, the overall perceived social support level significantly decreased from the prior-to-intervention phase (M = 138.54, SD = 10.77), to the post-dermatological-treatment phase (M = 133.89, SD = 10.54), p < .001 (see Table 2). These results were unexpected, but the similarities in lower perceived social support among groups can be attributed due to environmental conditions. More precisely, the follow-up research phase was conducted during summertime. During the summer period, most of the individuals (dermatological patients, as well as the control group) appeared to be more preoccupied with their appearance, and therefore they did not seem to rely on their social support network.

Table 2: Mean values of the overall scales of Rosenberg Self-esteem and ISEL-40 questionnaires, prior and post-dermatological treatment

|

|

Acne Group |

||||

|

Scales |

Prior to dermatological treatment phase |

Post- dermatological treatment phase |

|

||

|

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

p |

|

Overall ISEL-40 |

106,17 |

14,21 |

103,52 |

13,64 |

p<.001*** |

|

Overall Rosenberg |

24,81 |

1,79 |

24,87 |

2,09 |

p>.05 |

|

|

Psoriasis/Eczema Group |

||||

|

|

Prior to dermatological treatment phase |

Post- dermatological treatment phase |

|

||

|

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

p |

|

Overall ISEL-40 |

115,26 |

14,24 |

113,74 |

14,24 |

p<.001*** |

|

Overall Rosenberg |

25,94 |

2,15 |

25,68 |

2,38 |

p>.05 |

|

|

Control Group |

||||

|

|

Prior to dermatological treatment phase |

Post- dermatological treatment phase |

|

||

|

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

p |

|

Overall ISEL-40 |

138,54 |

10,77 |

133,89 |

10,54 |

p<.001*** |

|

Overall Rosenberg |

26,50 |

2,21 |

26,76 |

1,84 |

p>.05 |

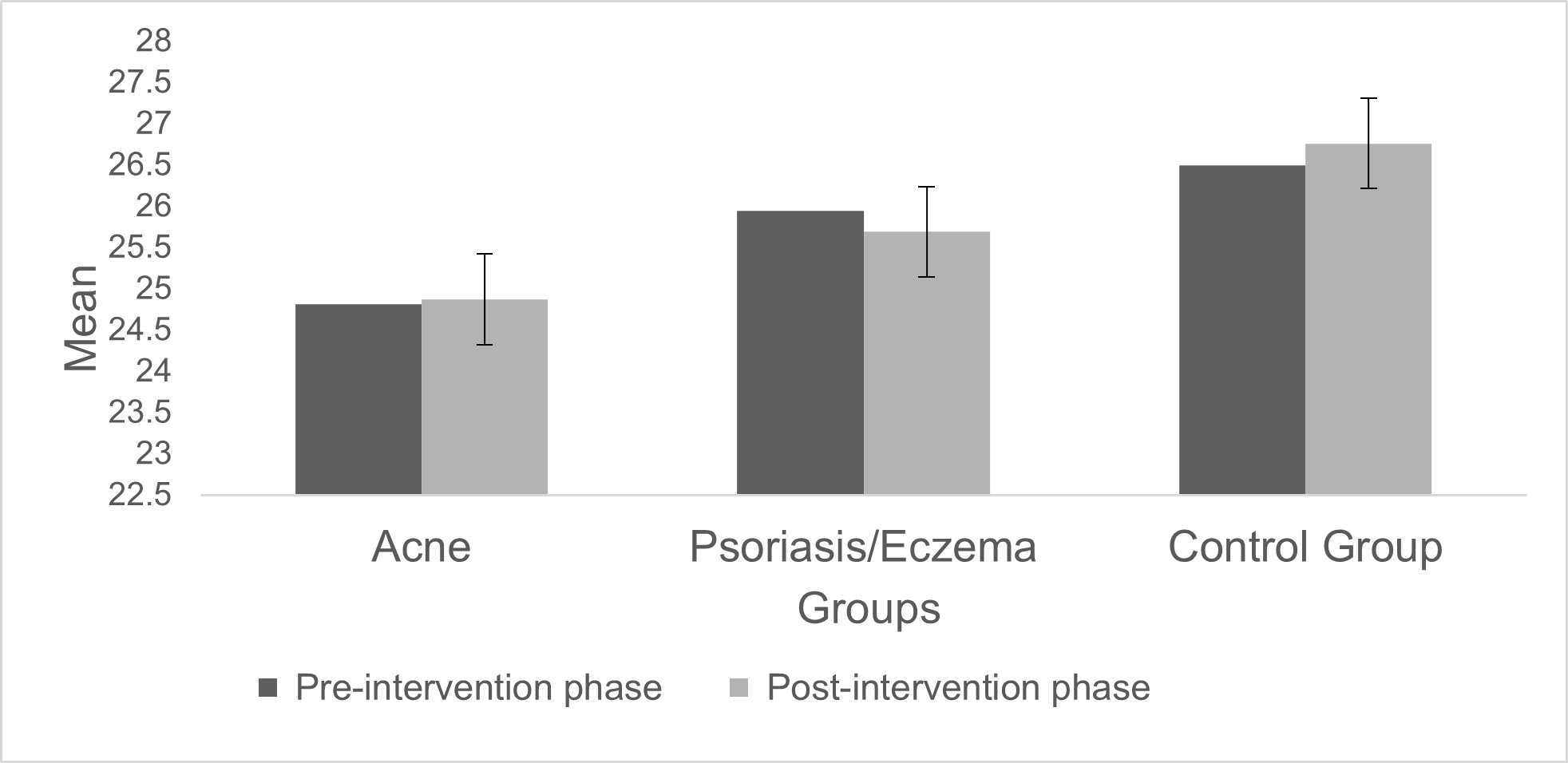

Also, analysis revealed a significant interaction effect between Time and Group, F (2,159) = 83.88, p <.001, η2 = .513. More specifically, it was observed that the groups of dermatological patients appeared to have lower levels of overall perceived social support, compared to the control group (p <.001), both at prior to- and at post-dermatological-treatment phase. Also, the groups of dermatological patients differed significantly from each other (p <.001), as patients with acne exhibited the lowest levels of overall perceived social support, both at prior to- and at post-dermatological-treatment phase (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Changes in overall perceived social support levels among the Groups, at prior to Dermatologists’ pharmacological intervention phase and at post intervention phase

Differences in overall self-esteem (Rosenberg Self-esteem scale) between groups, prior to- and post-dermatological treatment

The interaction between the two factors (Time and Group) is not statistically significant (p = .42), suggesting that the participants of the groups do not respond differently to the effect of Time (before and after completing their dermatological treatment), as far as their overall self-esteem levels are concerned (F(2,159) = .88, p >.05, η2=.011). Follow-up pairwise comparisons reflected that in Group A the overall self-esteem level did not change significantly from the prior- to-intervention phase (M = 24.81, SD = 1.79) to the post-dermatological-treatment phase (M = 24.87, SD = 2.09), p > .05. Also, for the participants of Group B, the overall self-esteem level did not change significantly from the prior-to-intervention phase (M = 25.94, SD = 2.15), to the post-dermatological-treatment phase (M = 25.68, SD = 2.38), p > .05. Similarly, in the control condition the overall self-esteem level did not change significantly from prior- to-intervention phase (M = 26.50, SD = 2.21), to the post-dermatological-treatment phase (M = 26.76, SD = 1.84), p > .05 (see Table 2).

However, a statistically significant main effect of the independent factor Group was observed, F(2,159) = 13.05, p <.001, η2 = .141. More specifically, the overall self-esteem differed significantly between patients with acne and the control group (p <.001), but also between patients with psoriasis/eczema and the control group (p = .02), with dermatological patients exhibiting the lowest overall self-esteem levels, both at prior to- and at post-dermatological-treatment phase. Furthermore, the overall self-esteem level also differed significantly between the groups of dermatological patients (p = .006), with the group of acne patients having the lowest levels, both at prior to- and at post-dermatological-treatment phase (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Changes in overall self-esteem levels among the Groups, at prior to Dermatologists’ pharmacological intervention phase and at post intervention phase

In conclusion, the two groups of dermatological patients appeared to have lower levels of overall perceived social support and lower levels of overall self-esteem, compared to the control group, at both prior to- and post- dermatological treatment phases. Furthermore, the group of patients with acne had lower perceived social support and lower self-esteem in comparison with the group of patients with psoriasis/eczema, at both research phases.

Discussion

The results of the current study are the first in Cyprus which reveal the negative influence of acne, psoriasis and eczema on patients’ self-esteem and perceived social support. The strengths of the present study are based on the fact that it is the first in the literature which suggests the low self-esteem and low perceived social support of dermatological patients at two research phases, prior to and post dermatological treatment, as well as the first which compares the findings from two groups of dermatological patients with a control group.

With regard to perceived social support, the findings of the current study showed that dermatological patients with acne appeared to have the lowest perceived social support, compared to the other groups, both prior to and after the completion of their dermatological treatment, a factor which makes them a particularly vulnerable population. The results of this study appear to agree with those from previous studies which included a sample of acne patients3,23, as well with the findings of a study with a sample of acne and eczema patients24. The current study agrees with the aforementioned findings while it also shows that both groups of dermatological patients appear to have lower levels of perceived social support and lower self-esteem, in comparison with our control group, that do not seem to improve at post-dermatological-treatment phase. Therefore, dermatological intervention does not appear to have an impact on the way dermatological patients perceive the availability of a supportive network.

Furthermore, the findings of the current study showed that the groups of dermatological patients have low perceived social support at the prior to dermatological intervention phase, in comparison with the control group, which appears to remain low, even at post-intervention-phase. The decrease in perceived social support in all groups of participants at post-dermatological-treatment phase may be due to environmental factors, such as the fact that the post-intervention-phase was during the summer months. However, dermatological patients appeared to have lower perceived social support in comparison with the control group. This finding suggests that some of these dermatological patients could possibly benefit from receiving psychosocial interventions along with their dermatological treatment, in order to be able to investigate all informative material available to them, as well as the way they perceive themselves in relation to their significant others. The results of this study appear to agree with previous studies which included patients with psoriasis25, as well as with the findings of studies which included a sample of patients with psoriasis and eczema26–28.

In conclusion, since dermatological patients of both groups have lower perceived social support, compared with the control group, it seems that skin disorders may negatively affect patients’ overall perceptual behavior towards the outside world. In addition, due to the fact that patients with acne appeared to have the lowest perceived social support, we conclude that the visible anatomical localization of the dermatological disorder (face), may further affect the way a patient perceives himself and the others around him. More specifically, an influential role on the selectivity of the social perception of patients with acne, seems to be played by the fact that these patients are required to focus on their face much more often (due to the visible anatomical localization), before they engage in any social activity, rather than focusing on how they feel. We therefore conclude that when there is no visible specific dermatological disorder or when it can be covered with clothing, then the negative social perception is more incomplete, since the results of the current study show that patients with psoriasis appear to have low perceived social support compared with the control group, but is however higher in comparison with patients with acne, at both research phases.

Finally, the difference in perceived social support between the two groups of dermatological patients can be explained by the fact that patients with psoriasis/eczema are less likely to notice their body, as their skin disorder has no visible anatomical localization, in comparison with patients with acne who cannot constantly hide their face. Therefore, the selectivity of the social perception of patients with acne towards their skin disorder appears to be more stable.

With regard to self-esteem, the results of the present study show that low self-esteem is associated with the presence of the dermatological disorder of acne, since this group of patients presented the lowest levels compared to the patients with psoriasis/eczema, and especially to the control group. More specifically, the results of the present study show that even after the completion of their pharmacological treatment, the self-esteem levels of acne patients show no significant change. The current results appear to agree with other findings5,6, although they did not include a follow up assessment as the current study. Furthermore, the present study agrees with the findings of Mulder et al.11 and Magin et al.8, which shows the urgency of providing social support to a population that seems especially vulnerable to low self-esteem and comorbid psychological difficulties.

Finally, the present study agrees with the most recent findings that patients with psoriasis had the lower levels of self-esteem, in comparison with the control group15,16, as they are compared with the results gathered from two different research phases, prior-to and after the completion of the dermatological pharmacotherapy.More specifically, the present study suggests that the low-esteem levels of patients with psoriasis at the prior to dermatological intervention phase remain unchanged, even after the completion of their dermatological treatment. Thus, the present study compared the results with those of a second group of patients and demonstrates that patients with psoriasis have higher self-esteem compared with patients with acne. The current study reveals the urgency for Dermatologists to become educated about the complex psychological consequences of dermatological disorders such as acne, psoriasis and eczema, since these disorders affect patients at a vulnerable age (adolescence) and may have long-lasting consequences on their self-esteem, social support and emotional well-being.

Limitations

This study has a few limitations. The first limitation is that all patients with skin disorder, as well as participants of the control group were recruited from two Cypriot cities and larger and more diverse sample is necessary for the results to be able to generalize across different populations. Moreover, the sample size is another limitation of the study, which does not allow us the generalization of current findings to the general population of patients with skin disorders. Finally, although both tools used to assess self-esteem and perceived social support are validated measures, a clinical interview could have provided additional findings along with the self-reported questionnaires chosen for this study.

Even if there are some limitations in the current study, we believe that it contributes significantly to the field of psychodermatology and psychosomatics, in several ways. Initially, it is the first study known to the authors till date which compares findings from two different groups of dermatological patients (with visible and non visible localization of skin disorder) and in comparison with a control group. Secondly, it is the first which assesses self-esteem and perceived social support at two research phases, prior to dermatological treatment and at the completion of the pharmacological treatment (six months later).

Conclusion

Acne, psoriasis and eczema seem to influence negatively dermatological patients’ self-esteem, as well as the way they perceive their social supportive network. Results of the current study reveal that dermatological patients, and especially those whose skin disorder have a visible localization (acne patients), show lower levels of self-esteem, as well as lower levels of perceived social support, compared to a control group, both prior to dermatological treatment and at post-treatment phase. For this reason, the current study suggests that complex psychological consequences might be identified in some patients and addressed in comprehensive management of their condition.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants for their time and contributions to the study. We would also like to thank all Dermatologists for facilitating the recruitment of the study participants.

Ethical Approval

The Cyprus National Bioethics Committee approved the study procedure, as well as all the tools used (EEBK EΠ 2015.01.103).

Funding

This study received no funding.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest with respect to this publication.

References

- Trzesniewski KH, Donnellan MB, Robins RW. Development of self-esteem. In: Self-esteem. New York, NY, US: Psychology Press; 2013. p. 60–79. (Current issues in social psychology).

- Urpe M, Pallanti S, Lotti T. Psychosomatic factors in dermatology. Dermatologic clinics. 2005; 23(4).

- Al Robaee AA. Assessment of general health and quality of life in patients with acne using a validated generic questionnaire. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panon Adriat. 2009; 18(4): 157–64.

- Dunn LK, O’Neill JL, Feldman SR. Acne in adolescents: Quality of life, self-esteem, mood and psychological disorders. Dermatol Online J. 2011; 17(1).

- Uslu G, Åendur N, Uslu M, et al. Acne: prevalence, perceptions and effects on psychological health among adolescents in Aydin, Turkey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008; 22(4): 462–9.

- Tasoula E, Gregoriou S, Chalikias J, et al. The impact of acne vulgaris on quality of life and psychic health in young adolescents in Greece: results of a population survey. An Bras Dermatol. 2012; 87(6): 862–9.

- Mallon E, Newton JN, Klassen A, et al. The quality of life in acne: a comparison with general medical conditions using generic questionnaires. Br J Dermatol. 1999; 140(4): 672–6.

- Magin P, Adams J, Heading G, et al. Psychological sequelae of acne vulgaris: results of a qualitative study. Can Fam Physician. 2006; 52(8): 978–9.

- Fakour Y, Noormohammadpour P, Ameri H, et al. The effect of isotretinoin (roaccutane) therapy on depression and quality of life of patients with severe acne. Iran J Psychiatry. 2014; 9(4): 237.

- ŠimiÄ D, PenaviÄ JZ, BabiÄ D, et al. Psychological status and quality of life in acne patients treated with oral isotretinoin. Psychiatr Danub. 2017; 29(suppl 2): 104–10.

- Mulder MMS, Sigurdsson V, Van Zuuren EJ, et al. Psychosocial impact of acne vulgaris. Dermatology. 2001; 203(2): 124–30.

- Rieder E, Tausk F. Psoriasis, a model of dermatologic psychosomatic disease: psychiatric implications and treatments. International Journal of Dermatology. 2012; 51(1): 12–26.

- Magin P, Adams J, Heading G, et al. The psychological sequelae of psoriasis: results of a qualitative study. Psychol Health Med. 2009; 14(2): 150–61.

- Krueger G, Koo J, Lebwohl M, et al. The impact of psoriasis on quality of life: results of a 1998 National Psoriasis Foundation patient-membership survey. Arch Dermatol. 2001; 137(3): 280–4.

- Aydin E, Atis G, Bolu A, et al. Identification of anger and self-esteem in psoriasis patients in a consultation-liaison psychiatry setting: a case control study. Psychiatry Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017; 27(3): 216–20.

- Nazik H, Nazik S, Gul FC. Body image, self-esteem, and quality of life in patients with psoriasis. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017; 8(5): 343.

- Magin P, Adams J, Heading G, et al. Experiences of appearance-related teasing and bullying in skin diseases and their psychological sequelae: results of a qualitative study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2008; 22: 430–6.

- Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, et al. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2000; 51(6): 843–57.

- Wang HH, Wu SZ, Liu YY. Association between social support and health outcomes: a metaâanalysis. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2003; 19(7): 345–50.

- Moos RH, Moos BS. Life stressors and social resources inventory-adult form: Professional manual. PAR Odessa, FL; 1994.

- Anderson RT, Rajagopalan R. Development and validation of a quality of life instrument for cutaneous diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997; 37(1): 41–50.

- Janowski K, Steuden S, Pietrzak A, et al. Social support and adaptation to the disease in men and women with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2012; 304(6): 421–32.

- Krejci-Manwaring J, Kerchner K, Feldman SR, et al. Social sensitivity and acne: the role of personality in negative social consequences and quality of life. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006; 36(1): 121–30.

- Livea Lalji TL, Anto MM, Shojan A, et al. Research Journal of Pharmaceutical, Biological and Chemical Sciences. 2015.

- Picardi A, Mazzotti E, Gaetano P, et al. Stress, social support, emotional regulation, and exacerbation of diffuse plaque psoriasis. Psychosomatics. 2005; 46(6): 556–64.

- Khoury LR, Danielsen PL, Skiveren J. Body image altered by psoriasis. A study based on individual interviews and a model for body image. J Dermatol Treat. 2014; 25(1): 2–7.

- Ramsay B, O’REAGAN M. A survey of the social and psychological effects of psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1988; 118(2): 195–201.

- LEWIS-JONES S. Quality of life and childhood atopic dermatitis: the misery of living with childhood eczema. Int J Clin Pract. 2006; 60(8): 984–92.

- Beck CT. Study guide to accompany Essentials of nursing research: methods, appraisal, and utilization. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2006.

- Naderifar M, Goli H, Ghaljaie F. Snowball sampling: A purposeful method of sampling in qualitative research. Strides in Development of Medical Education. 2017 Sep; 14(3): 1-6.

- Rosenberg M. Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSE). Acceptance and commitment therapy. Measures package. 1965; 61(52).

- Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, et al. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Social support: Theory, research and applications. Springer; 1985. p. 73–94.

- Adonis MN, Demetriou EA, Skotinou A. Acute stress disorder in Greek Cypriots visiting the occupied areas. J Loss Trauma. 2018; 23(1): 15–28.